|

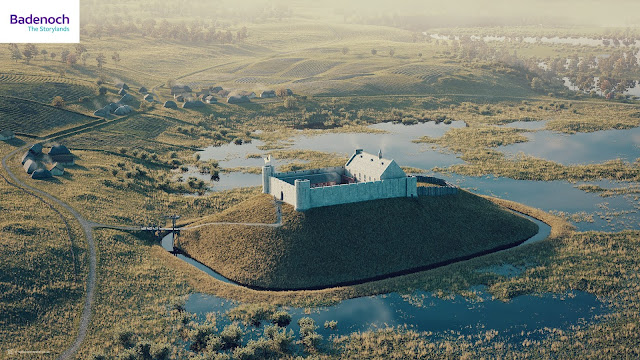

| Digital reconstruction of Ruthven Barracks (Bob Marshall) |

In summer 2020, I began work on a new project which was to create a series of visual reconstructions of some of Badenoch’s rich archaeological sites for Badenoch The Storylands. We published the first two of the reconstructions - Ruthven Barracks and Dun da Lamh hillfort - in the autumn of that year to promote the project and to announce that a new digital app was being developed by Whereverly in Edinburgh. The Badenoch The Storylands App is a self-guided touring aid, featuring walking, cycling, and driving tours around Badenoch, highlighting over 75 points of cultural heritage interest in the area.

My digital reconstructions were turned into Augmented Reality (AR) models for the app and optimised so that they could run efficiently on mobile/handheld devices. The 3D models that I developed were also used to generate a series of images and videos with much higher levels of visual detail. Here, I explain a little about each of the reconstructions and the digital models I developed for the project.

Ruthven Barracks and Castle

|

| Digital reconstruction of Ruthven Barracks (Bob Marshall) |

Built by George II’s government between 1719 and 1721 following the Jacobite rising of 1715, Ruthven Barracks housed infantry to enforce the Disarming Act of 1716. Although it is unlikely to have ever been fully garrisoned, the Barracks could hold two companies of soldiers – about 120 men – and their officers. On the orders of Major General Wade, a stable block was added to the west of the barracks in 1734, to be used by dragoons protecting troops marching along his military road.

|

| Digital reconstruction of Ruthven Castle, Badenoch c1398. © Bob Marshall |

Before the development of the eighteenth-century Government Barracks, at least two earlier castles stood at the top of this same great mound overlooking the River Spey. This digital reconstruction shows Ruthven Castle as it may have looked around the late fourteenth century. This is the castle occupied by Alexander Stewart, the 'Wolf of Badenoch', who likely adapted this from an earlier stronghold belonging to the powerful clan Comyn. Accurately reconstructing this earlier castle is difficult because the Wolf of Badenoch's castle was then rebuilt by the Earls of Huntly - Chiefs of Clan Gordon - before being demolished and replaced by military barracks at the time of the Jacobite uprisings. My visual interpretation is partially influenced by the castles at Balvenie at Lochindorb - also former strongholds of the Comyns which were forfeited after the clan lost power when Robert I seized the throne in 1306.

|

| Digital reconstruction of Ruthven Castle, Badenoch c1398. © Bob Marshall |

|

| Ruthven Castle - Digital Model. © Bob Marshall |

Raitts Township

|

| Digital reconstruction of Raitts Township, Badenoch (early-mid 1700s). © Bob Marshall |

Easter Raitts is a post-medieval township near Kingussie. My reconstruction shows how the settlement may have looked in the early-mid 1700s. The locations of the structures are carefully matched to survey drawings carried out by AOC Archaeology in 1995 (HER Monument MHG4411). The data from this survey was used to reconstruct the township at the nearby Highland Folk Park in Newtonmore, and which in turn has inspired my visual interpretation.

Digital model...

Alvie Ring Cairn

|

| Digital reconstruction of Alvie Ring Cairn, Badenoch. © Bob Marshall |

This reconstruction of the chambered cairn monument at Easter Delfour near Alvie, is part of a well-defined group of stone-built monuments found around the Moray Firth and Central Highlands, the so-called 'Clava cairns'. It comprises a circular cairn with a platform on the outside, bounded by a ring of monoliths or standing stones. Here I combined survey data with influences from the Balnuaran of Clava near Culloden - one of the best-preserved Bronze Age cairns in Scotland.

Digital model...

|

| Alvie Ring Cairn Monument |

Torr Alvie

|

| Digital reconstruction of Torr Alvie Hillfort, Badenoch (late Iron Age). © Bob Marshall |

A speculative digital reconstruction of Torr Alvie hillfort. Although the site has never been excavated, the line of its rampart walls can broadly be determined by a stony bank that encloses an area of roughly 85m x 30m. It is similar in size and shape to Craig Phadrig hillfort near Inverness. However, unlike Craig Phadrig, there is no evidence that Torr Alvie was vitrified. It is difficult to know how thick the ramparts were, whether there were timber palisades, or how many entrances there were, so imagination plays a large part in this visualisation.

|

| Digital reconstruction of Torr Alvie Hillfort, Badenoch (late Iron Age). © Bob Marshall |

Digital model...

Raitts Souterrain

Known locally as Raitts Cave, this horseshoe-shaped subterranean chamber (souterrain) was first discovered in 1835 (MHG4405 - Raitts Cave). My digital model was created by referencing Lidar scan data provided by Historic Environment Scotland. We do not have the evidence to reconstruct what might have existed above ground, so I have speculatively shown the hypothetical relationship between the souterrain and an early roundhouse dwelling. I cannot be certain whether the chamber was accessed from within the roundhouse, or externally, so this interpretation should not be considered conclusive. I have attempted to illustrate something of early domestic life and what the souterrain would have been used for - in this case, for the safe storage of food and other valuables.

This cutaway view showing the interior of the roundhouse and the subterranean chamber was one of the more challenging of the Badenoch reconstructions to create. I wanted to communicate the chamber within the context of the land above it and this had also to work effectively as a lower-detail AR model for use in the mobile app.

Dun da Lamh

|

| Digital reconstruction of Dun da Lamh hillfort, Badenoch (late Iron Age). © Bob Marshall |

Technical information

All of these reconstructions have been created using a variety of different software packages. For the most part, I used the open-source software Blender 3D and E-Cycles for the modeling and rendering of scenery and assets. Adobe Substance Painter and Photoshop were used for texturing detail and post-render digital painting. Height data was purchased from Ordnance Survey to create some of the landscapes and I used QGIS to combine this with geo-referenced archaeological data where this was available. World Machine was used with imported height-maps to generate the backdrop of the Cairngorm Mountains for my reconstruction of Torr Alvie hillfort.

Acknowledgments

I wish to end by offering a big note of thanks to the following people who generously gave assistance and feedback throughout this project: Eve Boyle, Adam Welfare, Iain Anderson, and Georgina Brown at Historic Environment Scotland. Prof. Richard Bradley of the University of Reading for his wisdom and advice on ring cairns and bronze age monuments. Matt Ritchie of Forestry Commission Scotland and Prof. Gordon Noble of the University of Aberdeen for their input and feedback on Dun da Lamh and Torr Alvie hillforts. Geoffrey Stell and Simon Forder for their assistance with Ruthven Barracks and Castle. I would also like to thank my clients, Badenoch Heritage, Cairngorms National Park Authority, and Voluntary Action in Badenoch & Strathspey, for inviting me to work on these reconstruction visuals and for allowing me the time to make these as detailed as possible. I hope that they will inspire people to visit Badenoch and take an interest in its rich heritage.

Finally, a posthumous thank you to the late Dr. Oliver O'Grady, who sadly and unexpectedly passed away just a month or so before this project commenced. Olly was project officer for Badenoch Great Place Project, he inspired and guided several of my previous visual reconstructions and introduced me to the world of hillforts. I hope my work here has done you proud, my friend.